Testing Artificial Intelligence

Building a python agent to pass IQ tests.

Background

In the summer of 2016 I started my Master’s degree in computer science. To be honest, I really didn’t know what I had gotten myself into. Luckily I started my degree with one of the top rated courses, Knowledge Based Artifical Intelligence - Cognitive Systems, run by the talented David Joyner. Throughout the semester I designed and built software that passed the Raven’s Progressive Matrices.

The idea behind using Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM) is that it is a great test of fluid intelligence - the ability to generalize and reason abstractly. A lot of research in deep learning currently focuses solely on identifying objects (computer vision), but this is only useful because there is normally a human doing the reasoning after the neural network has done the recognition. To build a generalized intelligence we need to consider how to architect software to perform visual reasoning.

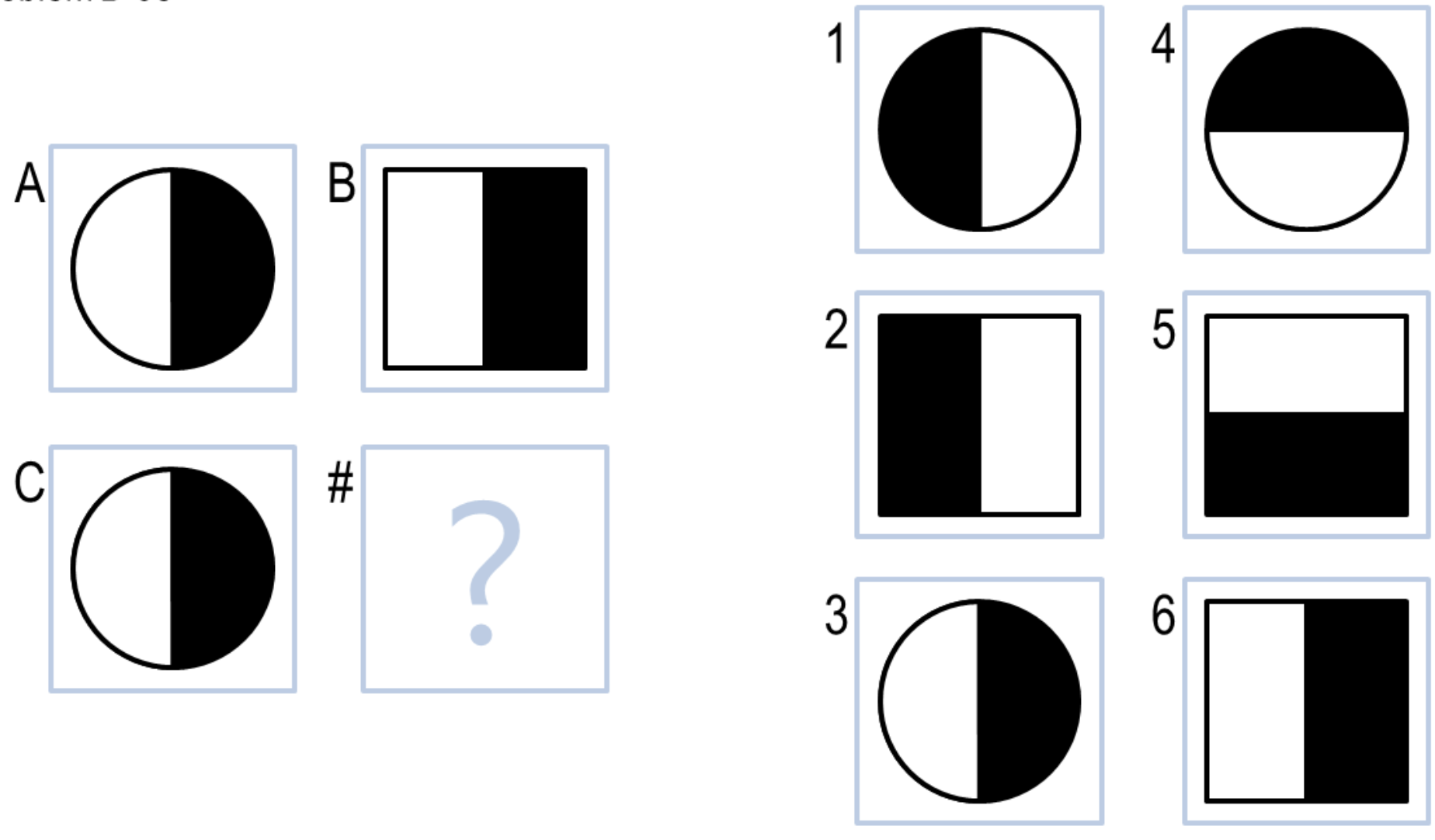

The project was performed in three iterations, with the first iteration only needing to pass 2x2 RPMs.

Verbal reasoning

For the first iteration I used a verbal reasoning method - the visual matrix was accompanied by a text representation that essentially solved the ‘correspondence problem’ for me - the problem of identifying which object in one box corresponded to which object in another box. The basic steps I took were as follows:

-

Ingest/Parse the problem A very simple ingestion of the data to convert the RPM into more easily manipulated data structures. Angle and size values were converted into integers, and alignments were converted into booleans.

-

Get objects from each figure This was a further round of parsing to represent the positional aspects of the objects with respect to each other.

-

Calculate transforms In this step I calculated the simplest transforms that converted the top left objects into the top right objects.

-

Compare all possible answer transforms (generate and test) For every single transform that was present in the A => B transform pipe that was also present in the C => answer transform pipe, the similarity score of that total transform was incremented. Thus each possible answer box was represented by a transform pipe with a score of how similar it was to the A => B transform pipe, allowing me to select the answer with the highest score.

This agent had difficulty with identifying reflection transformations, instead preferring to view them as rotations, as well as considering vertical relationships (the relationship between A and C, and B and #)

Visual reasoning

For the next two iterations I had to move to visual representations of the problem - I was losing too much information in trying to represent a complex environment with text descriptions. At its core, the visual agent uses pixel-based heuristics to pick the most likely answer. It first converts all figures to numpy arrays of pixels. It then captures the changes in the arrays between figures in the problem. It then uses a generate and test method to compare the transform required for each candidate answer with the training transforms, picking the candidate answer with the most similar transform.

What does any of this tell us about human cognition?

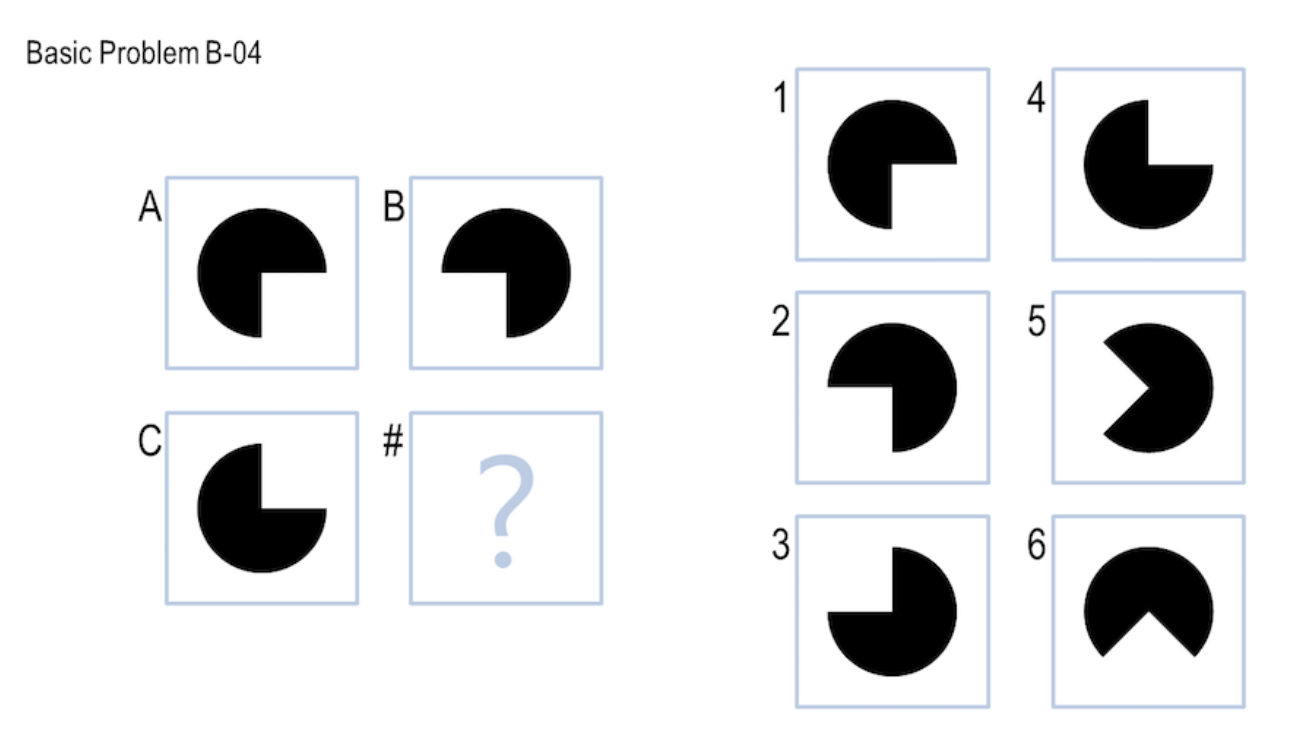

This project has made it abundantly clear to me how holistic and multi-layered the human method of reasoning is. The pac-man problem is an excellent example - humans do not consider rotations, reflections, black pixel ratios or overlap, or indeed any transformations between the figures.

Rather, the problem is solved because the correct answer produces the corners of a square that lies between A, B, C, and #. The figures together necessitate answer 3 as the correct response because it completes the gestalt. My agent does not consider anything greater than its current area of focus (a single figure and its immediate neighbor). Thus, the human reasons at multiple levels of abstraction, and has multiple strategies for solving RPMs. These strategies can be based on simple transformations, arithmetic (number of points on an object), semantics, or any other number of strategies.

Clearly, though, humans do not explicitly count pixels or determine overlap between figures. However, at a higher level of processing, you could argue that they do employ some kind of method similar to pixel counting - what my agent sees as an increase in the number of pixels, a human solver sees in more semantic terms (e.g. the square has got bigger or a new object appeared). The pixel overlap metric could be considered to be a very primitive part of a solution to the correspondence problem - where my agent sees a group of pixels that occupy the same space in two different figures, a human would see objects that correspond to one another based on their position in the figures.

One aspect in which my agent is clearly different from human solvers is that it is incapable of generating its own answer and then checking if this answer is available in the list of choices. In the pac-man example, the human generates an appropriate answer and then tests it against all possible answers. Only for more difficult tests is each possible answer is viewed in turn to see if it fits - thus the human is very capable of switching the form of generate and test that is being used.

It is clear to me that human solvers use multiple methods to solve problems. While my verbal agent represents the higher-level reasoning of a human solver, my visual agent represents the very low-level processing that the visual cortex would do. There is no reason that these two processes could not be simultaneously run. In fact, if a Raven’s problem that was simply random pixels (with no definable shapes) was presented to a human and the human were asked to describe their reasoning, surely their reasoning would involve picking an answer based roughly on black pixel count and black pixel overlap?

Thankfully, the voting nature of my project made it easy to extend with different strategies. Some of the more challenging problems were sufficiently tricky that I had to consider what relationships I saw in the problem, and then try and code a way for the agent to also recognise them. In this way, the agent multiplies the votes resulting from a certain relationship, if the salience of that relationship is sufficiently high. For example, if a horizontal XOR progression is seen in the figures at a high significance level, all votes from this relationship are multiplied. If a diagonal relationship is very significant (i.e. all the diagonal relationships are close to 100%, while the horizontal and vertical relationships are not), then diagonal votes are multiplied.

All of these processes work simultaneously, so the multipliers may be changed for all the relationships. What falls out of the calculations at the end is simply an array of votes for each possible answer. In this way, some relationships simply ‘pop’ out at the agent, in the same way that some relationships just jump out at the human viewer. The multipliers are simply a way of scoring the salience of relationships to humans.

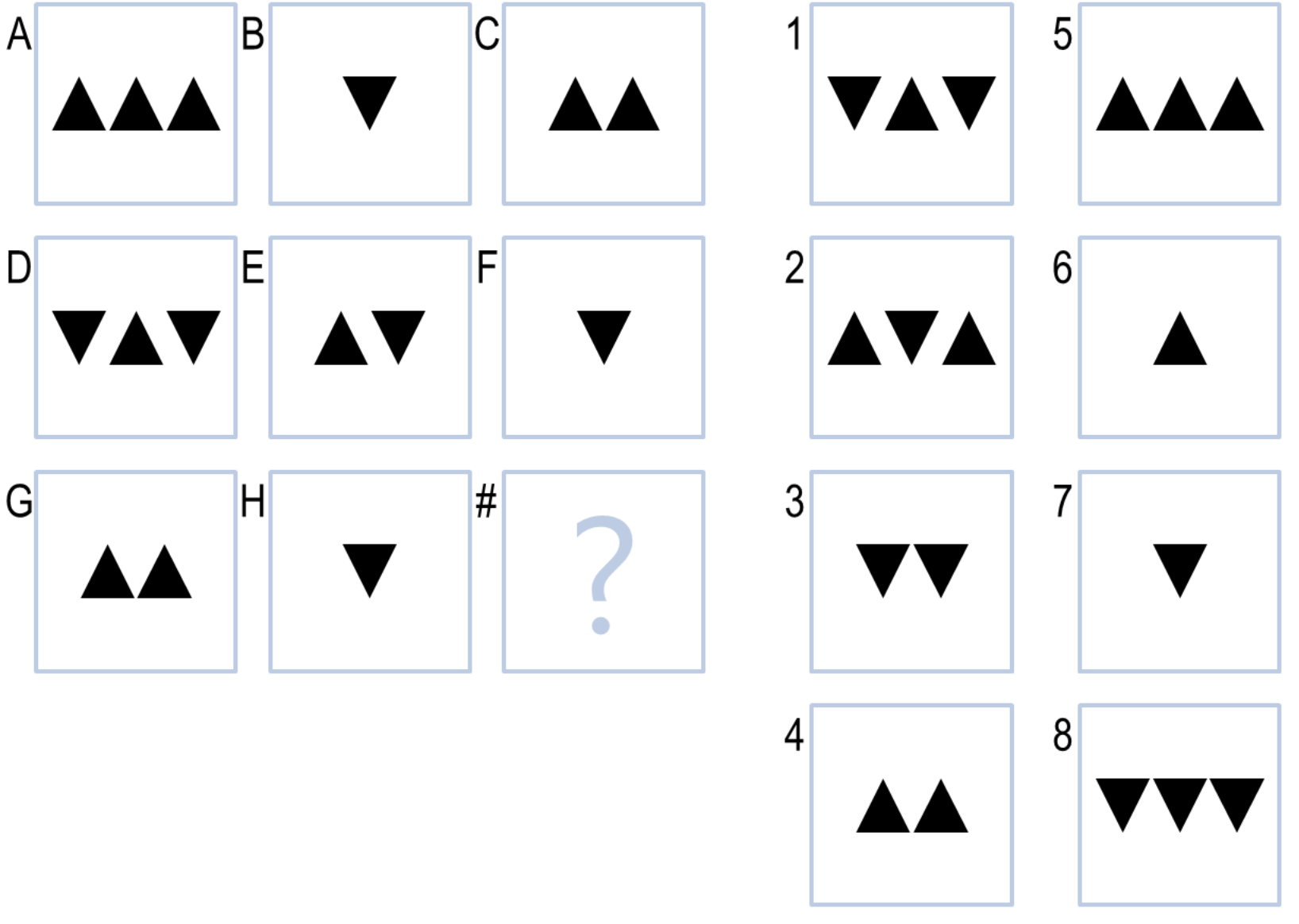

I found the last problem (shown below) most interesting.

I initially described its solution to myself by giving each object a meaning - an up triangle represented +1, and a down triangle represented -1. Simple addition and subtraction then gave the answer. I initially thought that there was no way my agent would be able to pick the answer. I only consider ‘up’ to be positive because that’s the way humans commonly represent numbers, and I only consider the triangle to be pointing in a certain way because I am used to seeing directions and arrows drawn like this. My agent has no background semantic knowledge to apply. I was then surprised to see my agent get the right answer using only pixel based heuristics.

This pretty much summed up the series of projects in this course for me - the ability of humans to very quickly use different strategies to see patterns and apply meaning to things, and the ability of AI agents to achieve complexity from very simple precepts. Clearly, the agent does not understand the meaning I have applied to the figures, and yet it achieves the same result from very simple heuristics.

Read the full project reflection here.